Have you ever wondered how discrimination shapes our behaviors and self-perception? Jane Elliott’s controversial classroom experiment holds the key. This landmark study, conducted in 1968, took a unique approach to teach her students about racism and prejudice by giving them a direct experience of discrimination. But even though this experiment took place decades ago, it remains incredibly relevant today in understanding human behavior, systemic bias, and the impact of stereotypes.

The Experiment in Brief: Dividing the Class, Creating Prejudice

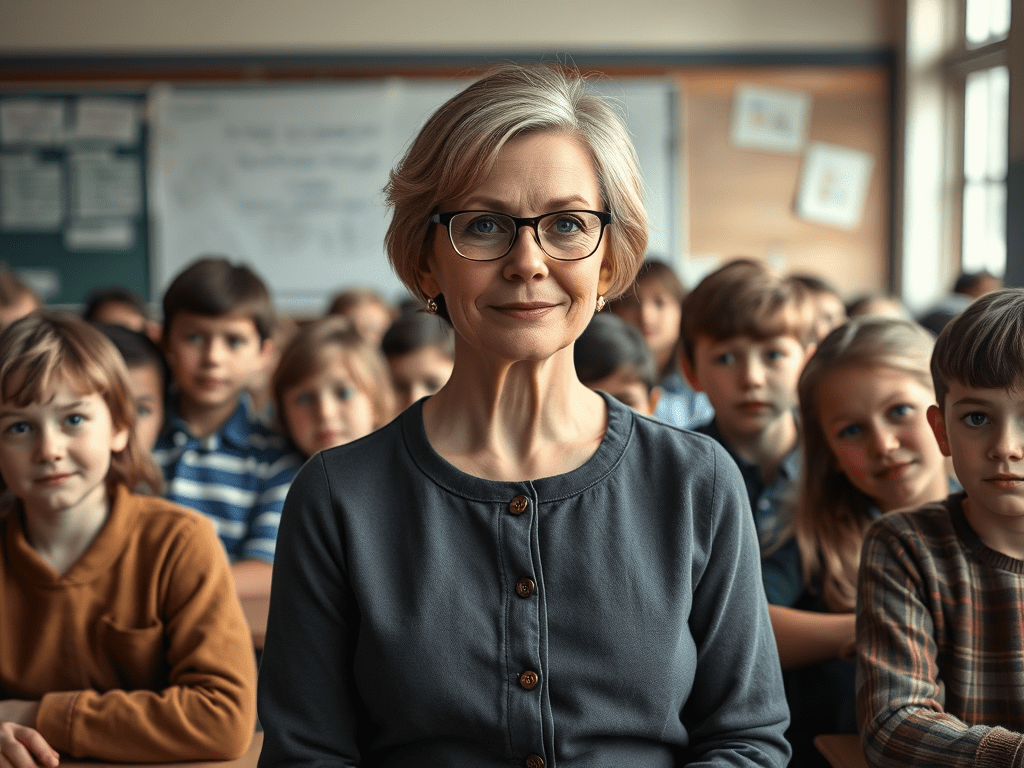

In the wake of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, third-grade teacher Jane Elliott wanted to help her class understand the deep-seated effects of racism and discrimination. To do so, she conducted the now-famous Blue Eyes/Brown Eyes experiment. Elliott divided her class into two groups based on the color of their eyes,blue and brown. On the first day, she told the students that those with blue eyes were superior to those with brown eyes.

She reinforced this belief by offering privileges to the blue-eyed group, more recess time, the best seats in the class, and praise for their intelligence. Meanwhile, the brown-eyed group was subjected to negative stereotypes. They were told they were less intelligent, less capable, and had to wear fabric collars to mark their “inferior” status. The students were treated differently based solely on this arbitrary classification.

The next day, Elliott reversed the roles, switching the privileges and labels. This manipulation helped her observe how easily children could adopt discriminatory behavior and how their performance was shaped by these labels.

Key Takeaways from the Experiment: How Labels Shape Behavior

How Jane Elliott Created Groups and Prejudice:

The key to Elliott’s success in shaping prejudice was her authority as a teacher. She used her position to create a system in which one group felt superior and the other inferior, simply based on eye color. By manipulating the environment, she highlighted how quickly people can internalize these labels.

Behaviors of In-Group and Out-Group:

When children were assigned the superior role (blue-eyed group), they became more confident, dominant, and even meaner. They started teasing the out-group, bullying them, and performing better academically, largely due to the privileges they were granted. The blue-eyed children also became more outspoken, showing that their perceived superiority boosted their confidence in ways that were evident both in their behavior and performance.

Conversely, the brown-eyed children, as the out-group, experienced lower self-esteem, anxiety, and stress. They became more withdrawn and showed signs of sadness. Their behavior reflected the negative labels they had internalized, proving how powerful societal messages about inferiority can be.

The discrimination even escalated to the point where one of the brown-eyed children punched a blue-eyed child in the gut because of the teasing, showing how quickly tension and frustration can build when one group is oppressed. This was a clear example of how prejudice and discrimination can lead to real conflict, even among children.

How These Labels Shape Expectations and Performance

As we saw in the experiment, the attributes assigned to each group directly shaped their performance and expectations. The in-group, when told they were superior, completed tasks at a faster pace, demonstrating higher confidence and motivation. On the other hand, the out-group took longer and struggled, as they were told they were inferior and less capable.

However, when the roles were reversed the next day, and the out-group became the in-group, they performed better than the previous in-group. This shows how powerful internalized narratives can be. When people are told they are superior or inferior, they start to believe it. The environment and others’ treatment of them directly influence their self-perception and behavior, leading to changes in their performance.

The Relevance Today: Discrimination, Bias, and Human Behavior

Even though Jane Elliott’s experiment took place in the late 1960s, its findings are incredibly relevant today. Systemic oppression, racism, and discrimination continue to shape societal structures, and Elliott’s study serves as a reminder of how prejudice can be internalized and perpetuated.

The Connection to Housing and Other Systemic Issues:

In today’s society, discrimination is often subtle but still deeply ingrained in areas such as education, employment, housing, and healthcare. People from marginalized groups continue to face barriers and are often told, explicitly or implicitly, that they are “less than.”

For example, in housing, job opportunities, and even in education, discrimination continues to shape who gets ahead and who falls behind, just like how the brown-eyed children were given fewer privileges. This results in cycles of poverty and exclusion for marginalized groups. These systems reinforce false beliefs, like the idea that one group is inferior to another.

When people are repeatedly told that one group is lazier or less capable, those stereotypes become internalized, creating a false confirmation bias. People begin to believe the narrative of one group being superior to another, even when the real reasons for disparities might be rooted in inequalities in resources, opportunities, or historical context.

The Impact of Internalized Bias: A Broader Lesson

Elliott’s experiment also sheds light on the concept of internalized bias. Just like the brown-eyed children were told they were inferior, people who belong to marginalized groups can internalize these beliefs. When these stereotypes are constantly reinforced, they shape people’s self-perception and behavior. It’s a cycle that continues as these narratives are perpetuated in society, reinforcing the bias that one group is “better” than another.

In Elliott’s classroom, the children’s self-esteem and performance were directly shaped by the labels they were assigned. This is the same way biases about race, class, and ability shape how people see themselves in society. It reinforces the idea that when people from marginalized groups are given fewer opportunities and privileges, they are less likely to succeed, not because of inherent flaws, but because they are treated as if they are less capable.

Conclusion: A Lesson for Today

In a world where biases and stereotypes are still prevalent, Elliott’s experiment serves as a powerful reminder of how quickly we can be influenced by societal structures that place value on arbitrary characteristics.

Understanding the psychological impact of these systems of inequality is crucial if we hope to create a more equitable society. For psychology students and anyone interested in human behavior, this experiment teaches us how power dynamics can shape not just how we see others but how we see ourselves.

As a psychology student, learning about this experiment has broadened my understanding of how discrimination operates, not just in isolated incidents, but within the very fabric of society. It’s a lesson we can all learn from, and one we should work to address in our own communities.

I encourage you to watch the documentary if you haven’t already, whether you’re a psychology student or just someone who stumbled across this post.

Leave a comment