Economic growth is like trying to ride a bike, you need the right balance of investment and savings to keep moving forward. The Harrod-Domar Growth Model is one of the earliest attempts to explain what makes economies grow and why they sometimes struggle. Developed in the 1930s and 1940s, this theory highlights two key factors: how much a country saves and how efficiently it turns those savings into investments.

In this article, we’ll break down what the Harrod-Domar model teaches us about economic growth, why it matters, and where it falls short, all in a way that’s easy to grasp, even if economics isn’t your thing.

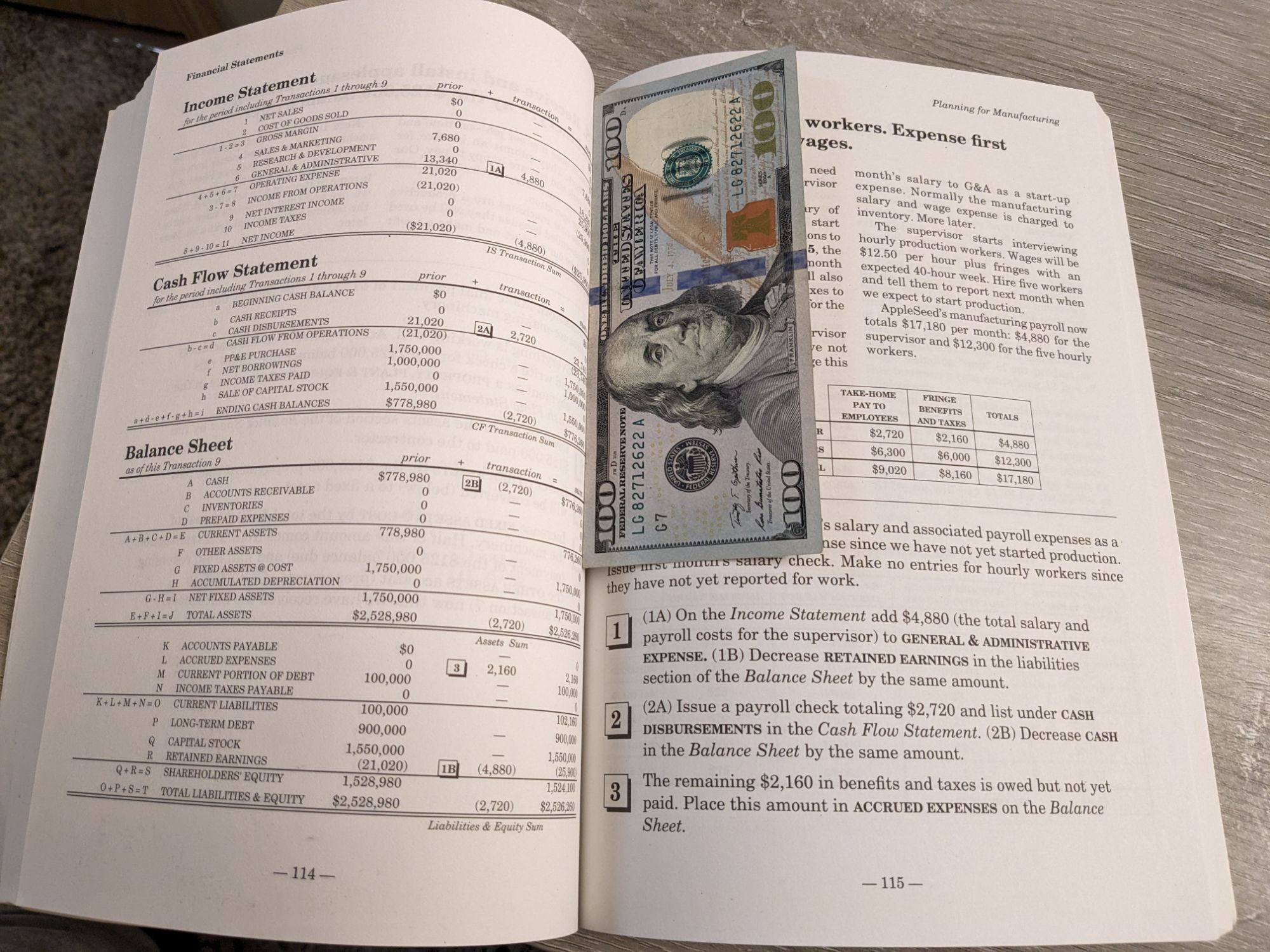

The Basics: What Is the Harrod-Domar Model?

Imagine you own a lemonade stand. You want to grow your business, but to do that, you need to buy more lemons, cups, and maybe even hire a friend to help. Where does the money come from? Either you save up from past sales or get an investment from someone else.

This is the core idea behind the Harrod-Domar model:

- Savings fuel investment. Countries that save more have more money available to invest in businesses, factories, and technology.

- Investment leads to growth. When money is used to buy equipment, hire workers, and build infrastructure, the economy expands.

But there’s a catch, if the balance between savings and investment is off, the economy can either boom unsustainably or slump into recession.

Key Lessons from the Harrod-Domar Theory

1. Economic Growth Needs Investment

The model teaches us that growth doesn’t happen magically. Countries need to reinvest their earnings into productive activities. For example, after World War II, countries like Japan and Germany focused heavily on rebuilding industries, fueling rapid economic expansion.

2. Savings Alone Isn’t Enough

While savings are necessary, they’re useless if not turned into productive investments. If people save money but banks don’t lend it out, or businesses don’t use it effectively, economic growth stalls.

3. The “Knife-Edge” Problem: Growth Is Unstable

Harrod and Domar argued that economies are fragile. If investment is slightly too high, the economy can overheat (causing inflation). If it’s too low, unemployment rises. This makes long-term stability difficult.

4. Developing Countries Struggle Without Capital

Many poor countries have low savings rates, which means they can’t invest in infrastructure, education, or industries. This explains why international aid and foreign investment play a major role in their economic growth.

Where the Model Falls Short

While the Harrod-Domar model explains some key factors in economic growth, it has limitations:

- It assumes all savings become investments. In reality, money can sit idle if businesses don’t see good opportunities.

- It ignores technological progress. Modern economies grow not just from investment but from innovation, like automation and digital transformation.

- It overlooks government policies and consumer demand. Factors like taxation, trade policies, and consumer spending patterns also influence growth.

Historical Example: Post-War Reconstruction and the Harrod-Domar Model

One of the best real-world examples of the Harrod-Domar model in action is the post-World War II recovery of Japan and Germany. Both countries had their economies devastated by the war, with industries destroyed, infrastructure in ruins, and massive unemployment. However, within a few decades, they became global economic powerhouses. How?

Japan’s Economic Miracle (1950s-1980s)

After World War II, Japan faced extreme poverty and economic instability. However, with financial aid from the U.S. (such as the Dodge Plan and Marshall Plan), Japan was able to channel massive investments into rebuilding its industries. The government encouraged high savings rates, which banks then directed toward industrial expansion. Using this investment-driven model:

- Japan heavily invested in infrastructure and manufacturing.

- Companies like Toyota and Sony grew by reinvesting profits into research and production.

- The economy experienced rapid GDP growth, often exceeding 10% per year in the 1960s.

This aligns with Harrod-Domar’s core idea: investment fueled economic expansion. Japan’s high savings rate and efficient use of capital created a cycle of growth that transformed it into a global economic leader.

Germany’s Post-War Recovery (1948-1960s)

West Germany followed a similar path. After WWII, its economy was in shambles. However, the introduction of the Deutsche Mark, combined with the Marshall Plan’s financial aid, helped kickstart investment.

- The government focused on rebuilding industries and infrastructure.

- Businesses reinvested capital into technology and production.

- A strong emphasis on exports further accelerated growth.

Between 1948 and 1960, Germany’s economy grew rapidly, proving that high investment and savings, core elements of the Harrod-Domar model, can drive recovery.

The Dodge Plan (Japan, 1949)

The Dodge Plan was a financial and economic reform strategy introduced by American economist Joseph Dodge to stabilize Japan’s economy after World War II. The plan aimed to:

- Control inflation by cutting government spending.

- Encourage savings to increase investment capital.

- Promote exports to drive economic growth.

By enforcing strict fiscal discipline and prioritizing industrial investment, the Dodge Plan helped Japan lay the foundation for its rapid economic expansion in the following decades.

The Marshall Plan (Europe, 1948-1952)

The Marshall Plan, officially known as the European Recovery Program, was a U.S.-led initiative to rebuild war-torn European economies. Its goals were to:

- Provide financial aid (about $13 billion) to help countries rebuild infrastructure.

- Revive industry and trade to prevent economic collapse.

- Counter the spread of communism by promoting economic stability.

West Germany was a major beneficiary, using these funds to invest in industrial growth, which helped accelerate its post-war recovery.

What Can the Harrod-Domar Model Teach Us About Personal Finance?

At first glance, the Harrod-Domar model seems like something that only applies to governments and big economies. But when you strip away the fancy economics terms, the core lesson is something we all deal with, balancing saving and investing to build a stable future.

Here’s how this model connects to real life, especially for those of us who live frugally, invest wisely, and want long-term financial freedom.

1. If You Want Growth, You Can’t Just Save—You Have to Invest

A lot of people think saving money is enough. But saving without investing is like piling up bricks without ever building a house. The Harrod-Domar model teaches that economic growth only happens when savings are converted into investment. The same applies to your personal finances.

How this fits my blog’s philosophy:

- Being frugal is great, but money sitting in a low-interest savings account is losing value to inflation.

- Smart investing, whether it’s dividend stocks, index funds, or even a side hustle, turns those savings into something that works for you.

- This is why I focus on investing as a broke college student, starting with small amounts, consistently, makes all the difference.

2. Living Below Your Means Fuels Your Future Growth

The Harrod-Domar model assumes that economic growth depends on how much a country saves and reinvests. If savings are too low, growth stalls. The same is true for individuals: if you spend everything you make, you’ll always be stuck in survival mode.

How this fits my mindset:

- I live like a broke college student even when I don’t have to, because keeping my expenses low gives me the freedom to invest more.

- The less you need to survive, the faster you can build wealth.

- Even when I had little, I prioritized investing a few dollars at a time because the earlier you start, the more time your money has to grow.

3. The “Knife-Edge” Problem: Balancing Risk and Stability

Harrod-Domar warns that if an economy invests too aggressively, it risks instability, but if it doesn’t invest enough, it stagnates. The same applies to personal finance: going all-in on risky investments can wreck you, but playing it too safe can leave you stuck.

How this fits my approach:

- I’m not here to YOLO all my money into meme stocks, but I’m also not afraid to put money into assets that will grow long-term.

- I don’t believe in just saving, I believe in stacking money in ways that make future me wealthier.

- The key is balance: having an emergency fund for stability while still making sure my money is working for me.

4. External Support Can Jumpstart Growth—If You Use It Right

Japan and Germany didn’t recover on their own after WWII, they got outside financial support (the Dodge Plan and Marshall Plan), but they used it wisely. This is the same reason why people who get financial help (grants, scholarships, stimulus checks, etc.) can either make it work for them or waste it.

How this fits my journey:

- I went to community college first to save money, then leveraged that into getting into a university, maximizing resources just like an economy receiving aid.

- If you get any extra money, whether it’s a tax refund, a one-time check, or even a raise, you can either blow it or reinvest it into your future.

- Financial aid, tax benefits, and even food stamps aren’t things to be ashamed of, they’re tools that, when used correctly, can help you break out of financial instability.

So, Is the Harrod-Domar Model Useful for Individuals?

Absolutely, but not in the way traditional finance gurus might say. It’s not just about “save and invest.” It’s about learning how to use what you have to create sustainable financial growth.

This model reinforces what I already believe:

- Saving is only useful if you do something with it.

- Living below your means isn’t just about sacrifice, it’s about giving yourself the power to build something bigger.

- Risk and stability have to be balanced, or you’ll either burn out or never grow.

- Resources exist, but it’s how you use them that determines your future.

At the end of the day, wealth isn’t built by just working harder, it’s built by understanding how to make money work for you. And that’s exactly what this economic model confirms.

Final Thoughts

The Harrod-Domar model isn’t just an economic theory, it reinforces key financial lessons:

- Saving is useless without investing.

- Living below your means gives you freedom.

- Growth requires balance between risk and security.

Understanding these principles can help anyone, whether a country or an individual, build a stronger financial future.

Leave a comment